Last Gasp Of The Old Warrior

Time is catching up with Mark Gastineau as he makes his case for Canton.

There isn’t much joy in being a New York Jets fan, that much I’m sure. And what joy there is, usually lies deep in the past, where outside of Super Bowl III, there were just brief flashes of promise from teams that always seemed to fall short of the big game.

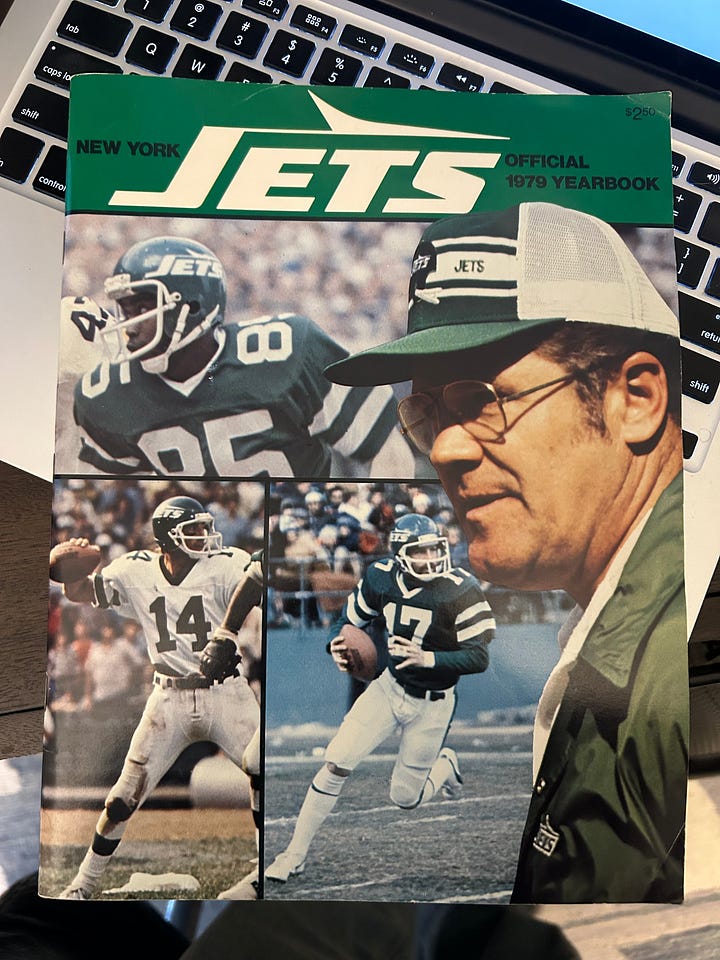

Such was the case of the New York Jets from 1978-1989, a period that straddled the end of an era at Shea Stadium and the start of another sharing the Meadowlands with the New York Giants. What the world remembers best from those years is the front four that terrorized quarterbacks in the early 80s: the New York Sack Exchange of Joe Klecko, Marty Lyons, Abdul Salaam, and most flamboyant of all, Mark Gastineau. Their story — where the showboating Gastineau is the lightning rod — was the topic of an ESPN 30 for 30 documentary that premiered Friday night at 8:00 p.m. EST.1

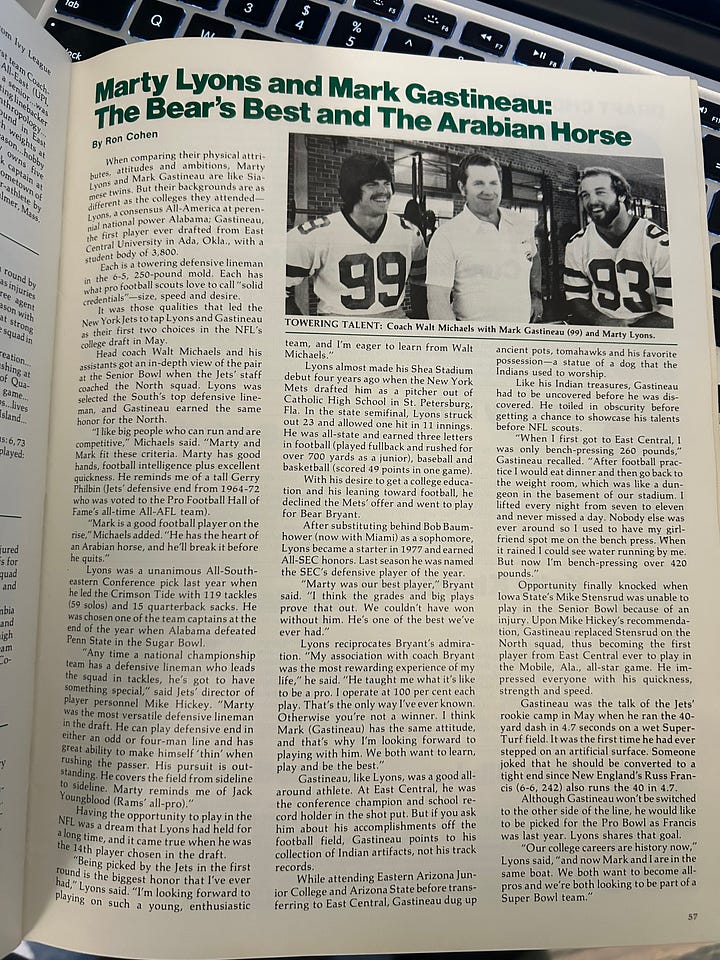

Gastineau joined the Jets as a second round draft pick in 1979 out of East Central Oklahoma. East Central was Gastineau’s third stop during his college career, which included short stints at Eastern Arizona and Arizona State before he settled in at the Division II school. It wasn’t exactly a football factory — Gastineau would be the first player from East Central to ever be selected in the NFL Draft — but after a strong performance in the Senior Bowl, the Jets opted to take him with the 41st overall pick, one round behind Marty Lyons, another defensive lineman who was far more heralded after playing four years for Paul “Bear” Bryant at the University of Alabama.

It wasn’t long after Lyons and Gastineau paired up with Klecko, a future member of Pro Football’s Hall of Fame, and Salaam, that Gastineau’s talent for getting to the quarterback entered full bloom. In 1981 the “New York Sack Exchange” was born, the brainchild of a New York Jets fan who had submitted the name to a team-sponsored contest. The Jets PR staff inserted the term into their press releases and the New York media blew it up, helped along by Gastineau’s “sack dances,” celebrations that electrified Jets fans at Shea Stadium yet rankled opponents to no end.

That November, the four were invited to the floor of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in Manhattan to ring the ceremonial opening bell. On the field, Klecko and Gastineau dueled for the league lead in the unofficial stat, with Klecko eventually edging out Gastineau by half a sack, 20.5 to 20.0. Knowing a good thing when they saw it, and with Lawrence Taylor involved in his own rampage with the Giants, the NFL began tallying sacks as an official statistic one season later in 1982.

Even then, there was evidence of strife on the Jets defensive line. Initially, the “Sack Exchange” hype machine was solely interested in recruiting Klecko and Gastineau, and it was only at Klecko’s behest that Salaam and Lyons were included. After all, Klecko concluded, the front four was a team. Without Lyons and Salaam clogging up the middle, the two defensive ends would never have a chance to get to the quarterback. And there was already talk that for all of Gastineau’s talent, he was a selfish, one-dimensional player, a criticism that often came, sotto voce, from Lyons.

Gastineau’s sack total dropped to six in the strike-shortened 1982 NFL season, one where the Jets made it to the AFC Championship Game before losing 14-0 to the Miami Dolphins on a muddy and rain-swept field in the Orange Bowl. But in 1983 and 1984, the Gastineau of old returned, while Klecko’s totals came down to earth. Gastineau tallied 19 in 1983, the team’s last season in Shea Stadium, and then 22 in 1984, the organization’s first playing in the Meadowlands. That mark would stand as the NFL record for almost 20 years. Gastineau recorded a respectable 13.5 sacks in 1985, but just two in 1986, where he made a mistake in the playoffs that lives on today.

Like it or not, it’s the signature play of his career.

Sneaking into the tournament with a 10-6 record, a season that ended with a five-game losing streak, the Jets took down the Kansas City Chiefs in the Wild Card Game at home, 35-15, the team’s first playoff game and win in New Jersey. That set up a matchup in the Divisional round vs. the Cleveland Browns at Municipal Stadium, one where the winner would advance to the AFC Championship Game.

With four minutes remaining in the game, the Jets took a 20-10 lead on a 25-yard touchdown run by Freeman McNeil. On the radio, the Jets play-by-play team erupted with joy, anticipating that a trip to the AFC Championship was in the offing. Even better, they would face the Denver Broncos, an opponent the Jets had handled easily earlier in the season, defeating them 22-10 at home on a Monday night in October.

The way to the Super Bowl seemed wide open. Until it wasn’t.

On the subsequent Cleveland possession with the Browns facing a second down with 24 to go from their own 18-yard line, a Bernie Kosar pass fell incomplete when the refs flagged Gastineau for roughing the passer. Instead of third down with 24 yards to go, the Browns took the 15-yard penalty and had a first down on their own 33-yard line. They would score a touchdown on the drive to cut the score to 20-17, and after forcing the Jets to punt on their next possession, Mark Moseley kicked a field goal with seven seconds remaining to tie the game 20-20 and send it to overtime. After a scoreless first overtime period where Moseley missed a chip shot field goal attempt, and the Jets moved into their patented “prevent” offense, he didn’t miss in the second overtime period, giving Cleveland a 23-20 win.2

After the game, Jets Head Coach Joe Walton and several of Gastineau’s teammates defended him in the press, but the NFL didn’t agree. Commissioner Pete Rozelle fined Gastineau $2,500 for what he termed to be a “flagrant blow.”

The following comes from a letter Rozelle sent to Gastineau levying the fine:

"You got by the left offensive tackle and charged directly at Kosar, who released the ball while you were still moving toward him with your head up … You then lowered your head and struck Kosar in the back with the crown of your helmet.

"As a defensive player and an eight-year veteran in the NFL, you should know that spearing a virtually defenseless player . . . is clearly against the rules and has been for many years. Such actions can cause serious injury to opposing players; they also have the potential of doing great harm to the tackler. Fortunately neither Kosar nor you was severely injured on the play."

The loss to the Browns is acknowledged to be one of the most heartbreaking in team history. And while Gastineau got cheers when he was inducted into the team’s ring of honor in 2012, I’m afraid the fans will never forget Cleveland. I know I haven’t.3

The following season, Gastineau angered his teammates when he crossed the picket line in defiance of a players’ strike against the owners. He said he needed the money. Klecko and Lyons soon followed. Seven weeks into the 1988 NFL season, Gastineau was leading the league in sacks with seven, when he announced he was retiring from professional football in order to tend to his fiancée, actress Brigitte Nielsen, who announced she had been diagnosed with uterine cancer.

One year later, Gastineau attempted a comeback with the British Columbia Lions of the Canadian Football League, but he was released after just four games. At age 33 after 10 seasons in the NFL, his career was over. What’s followed is a tale of woe that sports fans should be familiar with — a former athlete struggling to make a living out of the spotlight once the glory was gone and the money ran out.

The subsequent 35 years for Gastineau have been filled with drugs, brushes with the law and broken marriages. He’s 68, clearly laboring from the effects of CTE, and there are fewer days ahead than there are behind. He briefly surfaced in 2002, returning to the Meadowlands to be on hand in case Michael Strahan of the Giants eclipsed his single season sack record during the last game of the NFL regular season against Brett Favre and the Green Bay Packers.

With time running out, Favre — reportedly a friend of Strahan’s — called a bootleg where he ran more or less directly into the defensive lineman. Instead of trying to extend the play and escape, Favre slid to the turf to give himself up and let Strahan record the sack that broke Gastineau’s record. Watching at home, it was clear that Favre hadn’t put any effort into eluding Strahan, something that Gastineau took up with Favre in 2023 at an event in Chicago. Apparently, while he heartily congratulated Strahan at the time, the loss of income from no longer being able to claim the record as well as the harm he perceives it caused to his case for induction into the Hall has left Gastineau bitter. It’s a clip that ESPN has been blasting everywhere of late.

Favre has since taken to X to give his side of the story, and make the case that Gastineau deserves a place in Canton, something that he desperately wants after seeing Klecko inducted in 2023 after a long campaign. It was a classy gesture on Favre’s part, and more than Gastineau should have expected after acting so boorishly.

As to his candidacy for the Pro Football Hall of Fame, we need to remember that criteria for admittance to football’s hall of immortals is far more subjective than its counterparts in other sports. Joe Namath is the most important player in Jets history, and a consequential one in the history of pro football for helping engineer the win in Super Bowl III that proved the upstart American Football League (AFL) was the equal of the NFL. Yet many football fans credibly make the case that when you look at Namath’s numbers — he threw more interceptions than touchdown passes during his career — he doesn’t deserve a bust in Canton.

So when the votes are counted, intangibles matter. They can help get you in and they can keep you out — with the late Jack Tatum being just one example. In the case of Klecko, he was acknowledged as one of the league’s best defensive linemen at multiple positions in both the 4-3 and 3-4 alignment while he was still on the field. Several members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, including many of the offensive linemen who battled Klecko like Dwight Stephenson, Anthony Muñoz and Joe DeLamielleure stepped forward to support his candidacy. And even with all of that support behind him, he wasn’t inducted until 34 years after he retired.

In many ways Gastineau’s story parallels that of another New York sports superstar, retired Mets pitcher Dwight Gooden. He rocketed to the top of the baseball world, only for demons to unravel his career and almost take his life. In 2013, Gooden published a memoir. While his tale at times was revelatory — late New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner who was so often pilloried in the media turned out to be a hero through multiple attempts to help Gooden straighten out his life — I put it down without finishing the book. I simply couldn’t go on reading about how Gooden drove his life off the rails over and over, and I’m not sure I have much more of an appetite for it with Gastineau. I suspect that the voters in Canton won’t either.4

Salaam died this past October at age 71.

As opposed to the prevent defense, and just as effective when it comes to losing the game.

As for the NFL, they would prefer the hit disappear down the memory hole. I can’t find video of it anywhere. The NFL Films treatment of the game omits mention of it, even though the penalty was the lifeline the Browns needed to stay in the game. While NFL Films is rightly praised, there are other times when it can be downright Orwellian.

Earlier this year, Gastineau was included in an initial list of candidates in the “Senior” category for induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He failed to make the final cut.